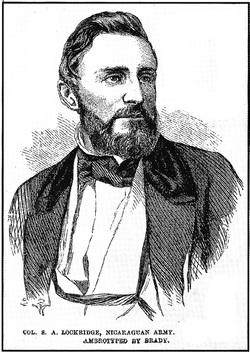

I meet a lot of interesting people doing research for historical fiction writing. Right now I’m working on a first draft of Valverde, a middle grade novel set in New Mexico during the Civil War. I’ve come across many colorful characters. The one who’s of interest to me right now is Samuel A. Lockridge, or at least that’s the name he was using when he was involved in the Civil War. Born in 1829, he was known as William Kissane in the 1850s, when he was a partner in the merchant firm of Smith and Kissane in Cincinnati, Ohio. In 1852 Kissane took out an insurance policy on a steamship named Martha Washington and its cargo. Soon thereafter the ship, its cargo, and sixteen people aboard it burned, and Kissane was charged with conspiracy. He posted $10,000 in bail, then disappeared. Around 1855 Kissane reappeared in Texas, but by now he was known as Samuel Lockridge. He joined forces with William Walker, an American physician, lawyer, journalist and mercenary, who gave him the rank of Colonel in his private army. Lockridge contributed $40,000, a considerable sum in those days, to help Walker recruit and equip a private military expedition into Latin America. Their intention was to establish an English-speaking colony under Walker’s personal control, an enterprise then known as "filibustering." Lockridge took 283 “Texas Rangers” to Nicaragua in late November of 1856, and was able to help Walker usurp the presidency of the Republic of Nicaragua. After a series of setbacks and several disagreements with Walker, Lockridge returned to Texas in August 1857. Soon thereafter, Walker was defeated by a coalition of Central American armies. The government of Honduras executed him in 1860. Once back in Texas, Lockridge joined the Knights of the Golden Circle, a secret Southern society that advocated the extension of Southern institutions into new territory. He was not a delegate during the Convention that debated Texas secession, but he carried dispatches from Howell Cobb, the President of the Confederate Congress. Lockridge joined the Fifth Texas Cavalry, one of the divisions in Sibley’s Army of New Mexico in July 1861 and became a Major. By that fall, Sibley's army was on the march. Their battle cry, "On to San Francisco!" showed their intention to take New Mexico as a stepping stone to the gold fields of Colorado, and the ports and gold of California. If Sibley would have succeeded, the Confederate States might have had the the prestige they needed to gain European allies and the capital to support their army better. A few nights before the Battle of Valverde, Lockridge was sitting around a campfire with his men, and one of them sang “The Homespun Dress,” a Confederate song about how much a southern woman would be willing to sacrifice for the cause. Lockridge bragged that he was going to pull down the Union flag from Fort Craig. He said that if he could get a wife as easily as he was going to get the flag, then he would never sleep by himself again, and he planned to make a dress out of the flag to present to his wife. On February 21, 1862 at the battle of Valverde, Lockridge led an assault on a battery of Union artillery. He and his men managed to cross the 800 yards between the Confederate line and the guns. He laid his hand on the muzzle of one of the cannons and shouted “This one is mine!” before being shot dead.  THE HOMESPUN DRESS by Carrie Belle Sinclair (born 1839) Oh, yes, I am a Southern girl, And glory in the name, And boast it with far greater pride Than glittering wealth and fame. We envy not the Northern girl Her robes of beauty rare, Though diamonds grace her snowy neck And pearls bedeck her hair. CHORUS: Hurrah! Hurrah! For the sunny South so dear; Three cheers for the homespun dress The Southern ladies wear! The homespun dress is plain, I know, My hat's palmetto, too; But then it shows what Southern girls For Southern rights will do. We send the bravest of our land To battle with the foe, And we will lend a helping hand-- We love the South, you know CHORUS Now Northern goods are out of date; And since old Abe's blockade, We Southern girls can be content With goods that's Southern made. We send our sweethearts to the war; But, dear girls, never mind-- Your soldier-love will ne'er forget The girl he left behind.-- CHORUS The soldier is the lad for me-- A brave heart I adore; And when the sunny South is free, And when fighting is no more, I'll choose me then a lover brave From all that gallant band; The soldier lad I love the best Shall have my heart and hand.-- CHORUS The Southern land's a glorious land, And has a glorious cause; Then cheer, three cheers for Southern rights, And for the Southern boys! We scorn to wear a bit of silk, A bit of Northern lace, But make our homespun dresses up, And wear them with a grace.-- CHORUS And now, young man, a word to you: If you would win the fair, Go to the field where honor calls, And win your lady there. Remember that our brightest smiles Are for the true and brave, And that our tears are all for those Who fill a soldier's grave.--CHORUS from http://www.civilwarpoetry.org/confederate/songs/homespun.html Samuel Lockridge is one of the real characters that plays a part in Jennifer Bohnhoff's novel Where Duty Calls, book one in the Rebels Along the Rio Grande Series of historical novels suitable for middle grade through adult readers. Jennifer Bohnhoff is an author and novelist who lives in the mountains of central New Mexico. You can read more about her here. |