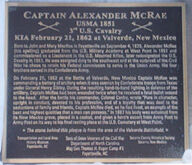

Families divided, brother against brother. It's one of the themes of the American Civil War. Alexander McRae's story is an example of it. Alexander McRae was born in Fayetteville, North Carolina on September 4, 1829. He had four brothers. A West Point Graduate, McRae served in Missouri and Texas before coming to New Mexico in 1856, He served at Forts Union, Stanton, and Craig. McRae also spent some time at Bent's Fort, in what is now Colorado. He steadily rose up the promotion ladder, becoming Captain of Company I, 3rd Cavalry Regiment in August of 1861. When the Civil War broke out, McRae's father wrote to him, urging him to change sides. Captain McRae retained his commission and stayed faithful to his country while his four brothers, James, Thomas, John, and Robert, served the Confederacy. As reports began to trickle into New Mexico of a Southern invasion, Colonel Edward R.S. Canby, the commander of forces in New Mexico Territory, hastily formed an artillery battery. He placed the six pieces at Fort Craig, the most southerly of the forts held by the Union Army, and gave Captain McRae charge of this unit.  McRae's battery performed with great success during the first hours of the Battle of Valverde, which took place at a Rio Grande crossing a few miles north of Fort Craig on February 21, 1862 . Finally, Confederate Colonel Thomas Green led a charge on the Union guns. Screaming the Rebel yell, the Confederate forces advanced in three separate waves that totaled nearly 750 men. The Rebels, armed with short-range shotguns, pistols, muskets, and bowie knives, watched for flashes from the artillery, then dove to the ground for cover. This strategy made them appear to be suffering a high casualty rate, yet they kept coming. This spooked the men manning the Union guns, particularly the inexperienced and ill-trained New Mexico Volunteers, who broke and splashed across the Rio Grande in a disorganized retreat. Despite McRae's remaining gunners firing shell and cannister as fast as they could, the Texans reached the battery. Fierce hand-to-hand fighting ensued as the Union soldiers sought to defend their position. Samuel Lockridge, a Texan officer reportedly shouted, "Surrender McRae, we don't want to kill you!" McRae supposedly replied, "I shall never forsake my guns!" Both Lockridge and McRae were killed in the melee, some sources suggesting by each other. The captured guns went to San Antonio when the Confederate forces retreated. They became known as the Valverde Battery and were used against Union troops for the remainder of the war.  Because he fought for the Union, McRae's service record went unrecognized in his home state. In their story on the battle at Valverde, the Fayetteville Observer did not even report his death. However, McRae became an honored figure in New Mexico history. There are streets named after him in the New Mexican towns of Las Cruces and Las Vegas, and a canyon named for him in Sierra County. The remains of Fort McRae, a late Civil War and Indian War Army post named for him, now lay beneath the waters of Elephant Butte Lake. I could find some earlier reports of it being a destination for scuba divers, but the adobe walls have probably succumbed to time and water by now. Alexander McRae's body was exhumed in 1867 and transported to West Point for burial. McRae’s large black tombstone is only four markers away from the one dedicated to George Armstrong Custer. Guides frequently note it as the resting place of one who stayed with the Union.  In his official report of the Combat of Valverde, Colonel Canby, wrote: Among the killed is one, isolated by peculiar circumstances, whose memory deserves notice from a higher authority than mine. Pure in character, upright in conduct, devoted to his profession, and of a loyalty that was deaf to the seductions of family and friends, Captain McRae died, as he had lived, an example of the best and highest qualities that man can possess. In time, the South also recognized Captain Alexander McRae. A marker now stands in front of the Old Historic Cumberland County Courthouse, which was built on land that was homesteaded by his grandparents.  While he is not a speaking character, Captain Alexander McRae's death is part of the battle scene in Jennifer Bohnhoff's novel Where Duty Calls, the first in a trilogy of novels set in New Mexico during the Civil War and telling the story from both the Union and Confederate side of the conflict. Book #2 is named The Worst Enemy and is also available. Book #3, The Famished Country, is scheduled to be published in the fall of 2024 by Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesia Publishing. |