Last week I wrote about American Presidents of Scots descent. This week, I’ll share some information on two more Scotsmen. One had a tenuous tie with the United States, the other had no connection to America, but they’re both interesting men, whose name has lived beyond them.

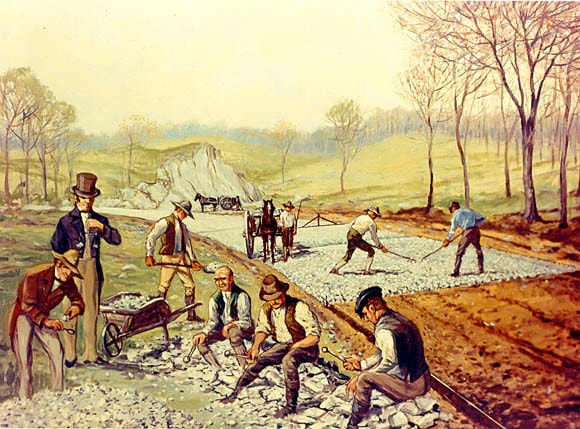

John Loudon McAdam was the inventor of “macadamisation,” an effective and economical method of constructing roads. Born in Ayr, Scotland in 1756, McAdam made his fortune working in his Uncle’s counting house in New York during the American Revolution. When he returned home in 1783, he bought an estate and began operating a colliery, some kilns, and an ironworks. These businesses gave him the technical knowledge to suggest that roads should be raised above the surrounding ground and constructed of systematically layered rocks and gravel. He wrote his conclusions in two treatises, Remarks on the Present System of Roadmaking (1816) and Practical Essay on the Scientific Repair and Preservation of Roads (1819).

John Loudon McAdam was the inventor of “macadamisation,” an effective and economical method of constructing roads. Born in Ayr, Scotland in 1756, McAdam made his fortune working in his Uncle’s counting house in New York during the American Revolution. When he returned home in 1783, he bought an estate and began operating a colliery, some kilns, and an ironworks. These businesses gave him the technical knowledge to suggest that roads should be raised above the surrounding ground and constructed of systematically layered rocks and gravel. He wrote his conclusions in two treatises, Remarks on the Present System of Roadmaking (1816) and Practical Essay on the Scientific Repair and Preservation of Roads (1819).

By Peetlesnumber1 - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21076588

By Peetlesnumber1 - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21076588In time, road builders began adding hot tar to bond the rocks and gravel together. This is what I’ve always called asphalt but depending on where you live it can be called macadam, blacktop, or tarmac, a mixture of the words tar and “macadam.

The first macadam road in North America was the National Road, also known as the Cumberland Road. Construction began in 1811, in Cumberland, Maryland, on the Potomac River. The road stretches 620 miles and connects the Potomac to the Ohio River. It was macadamized in the 1830s and became the main road for thousands of settlers moving west. The road ended in Vandalia, Illinois, 63 miles east of St. Louis, It would have gone further had not an 1837 financial panic led Congress to cut off funding.

The first macadam road in North America was the National Road, also known as the Cumberland Road. Construction began in 1811, in Cumberland, Maryland, on the Potomac River. The road stretches 620 miles and connects the Potomac to the Ohio River. It was macadamized in the 1830s and became the main road for thousands of settlers moving west. The road ended in Vandalia, Illinois, 63 miles east of St. Louis, It would have gone further had not an 1837 financial panic led Congress to cut off funding.

The other McAdam whose name has outlived him is Dr. John Macadam, who was born outside of Glasgow, Scotland in 1827. He taught university-level chemistry, first in Glasgow and then in Melbourne, Australia. He was also a medical doctor, a health official for the city of Melbourne and a member of the agricultural board. As a politician, he fought to make parliament enact food purity laws. The macadamia nut, a native plant of Australia, was named in his honor by the botanist Ferdinand von Mueller.

Here’s one of my favorite uses for macadamia nuts. I think Dr. John would have enjoyed them, and I hope you do, too.

Here’s one of my favorite uses for macadamia nuts. I think Dr. John would have enjoyed them, and I hope you do, too.

Chocolate Macadamia Cookies

¾ cup firmly packed brown sugar

½ cup sugar

1 cup softened butter

1 tsp almond extract

1 egg

2 cups flour

¼ cup cocoa

1 tsp baking soda

½ tsp salt

1 cup white chocolate chips

½ cup macadamia nuts, coarsely chopped

Preheat oven to 375°.

Beat sugars and butter until light and fluffy.

Add extract and egg and blend well.

Stir in flour, cocoa, baking soda and salt and mix well.

Stir in chips and nuts.

Drop by rounded tablespoonfuls, 2” apart on ungreased cookie sheets.

Bake at 375° for 8-12 minutes, or until set.

Cool 1 minute before removing from sheet to cooling rack.

Makes 2 ½ cookies.

½ cup sugar

1 cup softened butter

1 tsp almond extract

1 egg

2 cups flour

¼ cup cocoa

1 tsp baking soda

½ tsp salt

1 cup white chocolate chips

½ cup macadamia nuts, coarsely chopped

Preheat oven to 375°.

Beat sugars and butter until light and fluffy.

Add extract and egg and blend well.

Stir in flour, cocoa, baking soda and salt and mix well.

Stir in chips and nuts.

Drop by rounded tablespoonfuls, 2” apart on ungreased cookie sheets.

Bake at 375° for 8-12 minutes, or until set.

Cool 1 minute before removing from sheet to cooling rack.

Makes 2 ½ cookies.