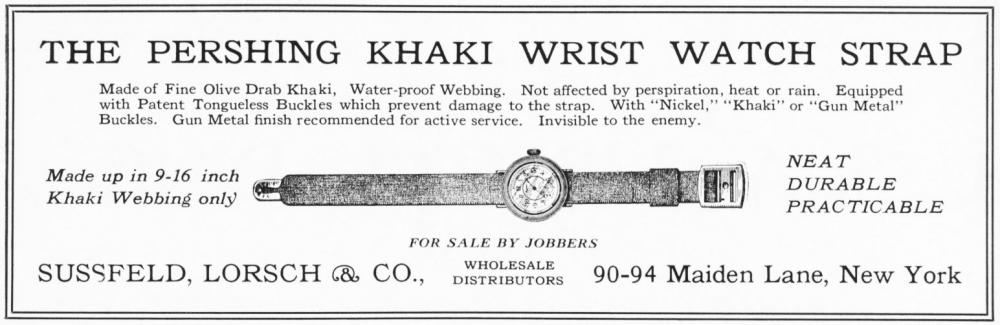

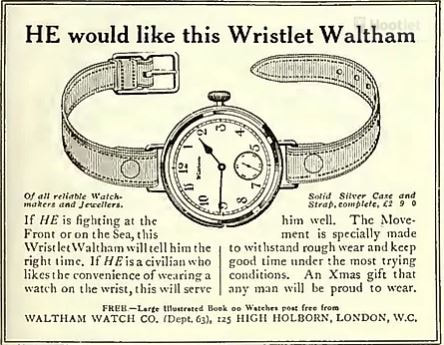

At the beginning of the twentieth century, wrist watches were feminine novelties worn by trendy women. By 1920, they had become standard military issue and symbols of masculine virility. This change came about because of the need to synchronize artillery and infantry during the First World War. Perhaps no one captured this change better than Edgar Albert Guest, the people’s poet whose poems filled the papers throughout the war. The Wrist Watch Man He is marching dusty highways and he's riding bitter trails, His eyes are clear and shining and his muscles hard as nails. He is wearing Yankee khaki and a healthy coat of tan, And the chap that we are backing is the Wrist Watch Man. He's no parlour dude, a-prancing, he's no puny pacifist, And it's not for affectation there's a watch upon his wrist. He's a fine two-fisted scrapper, he is pure American, And the backbone of the nation is the Wrist Watch Man. He is marching with a rifle, he is digging in a trench, He is swapping English phrases with a poilu for his French; You will find him in the navy doing anything he can, For at every post of duty is the Wrist Watch Man. Oh, the time was that we chuckled at the soft and flabby chap Who wore a little wrist watch that was fastened with a strap. But the chuckles all have vanished, and with glory now we scan The courage and the splendor of the Wrist Watch Man. He is not the man we laughed at, not the one who won our jeers, He's the man that we are proud of, he's the man that owns our cheers; He's the finest of the finest, he's the bravest of the clan, And I pray for God's protection for our Wrist Watch Man.  Jennifer Bohnhoff lives in the mountains of central New Mexico, where she writes historical fiction and spends way too much time finding interesting bits of history on the internet. You can read more about her and her books on her blog, https://jenniferbohnhoff.blogspot.com/ |