General John Joseph Pershing is the only person who has held the special rank of General of the Armies of the United States during his lifetime. (The only other people to have held this rank are George Washington, who was awarded it posthumously in 1976, and Ulysses S. Grant who received the honor in 2020.) His military career spanned several wars during the period when the United States was becoming a force to be reckoned with on the world stage. Through his many famous and talented protégés, his influence continued long after his retirement.

John Pershing as a young boy. [The Story of General Pershing, Everett T. Tomlinson, 1919,)

John Pershing as a young boy. [The Story of General Pershing, Everett T. Tomlinson, 1919,)Pershing was born on a farm in Laclede, Missouri on September 13, 1860. His mother was a homemaker and his father, John Fletcher Pershing, owned a general store and served as Laclede’s postmaster. During the Civil War, John Fletcher worked as a sutler, a civilian merchant who accompanied an army and sold goods to soldiers, for the Union. John Joseph was the oldest of nine children, six of which survived to adulthood. Pershing's family was not wealthy. Beginning at age 14, the oldest son was expected to contribute to the family. John began working. He also began putting aside money for his education, as his family had told him that schooling was not something they could afford.

John Pershing as a West Point cadet (Photo: public domain)

John Pershing as a West Point cadet (Photo: public domain)Pershing studied at Kirksville Normal School (now Truman State University), where he received his teaching degree in 1880. He taught African-American schoolchildren at Prairie Mound School, but became interested in law and went back to school to become a lawyer. When he decided that he could not get as good an education as he wanted in Missouri, he applied to the Military Academy at West Point, where cadets received a high-quality education for free in exchange for military service. At West Point, his leadership skills became apparent and he found himself in many command roles. He was the class president all four years. In 1885, when President Ulysses S. Grant’s funeral train passed West Point, Pershing commanded the honor guard.

After graduating in 1886, Pershing was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant. He reported for duty in 6th U.S. Cavalry Regiment in New Mexico, where he participated in several Indian War campaigns, including fighting the Apaches led by Geronimo.

Next, Pershing was posted to the University of Nebraska, where he taught military science. During his four years there, Pershing earned the law degree he’d so long wished for.

In 1896, he was promoted to 1st Lieutenant and assigned to a troop of the 10th Cavalry Regiment, one of the original regiments of Buffalo Soldiers, racially segregated black units. This began Pershing’s long association with black units.

In 1897, Pershing was sent back to West Point, where his strict ways with the students made him an unpopular teacher. The students nicknamed him Black Jack. By World War I, the epithet that was supposed to be derogatory had lost its sting and become popular. It remained with him for the rest of his life.

When the Spanish-American War broke out, Pershing was again selected to command the Tenth Cavalry, this time as their quartermaster. On July 1, 1898 he led his men in the Battle of San Juan Hill alongside Theodore Roosevelt’s famous Rough Riders.

Pershing later recalled that

...the entire command moved forward as coolly as though the buzzing of bullets was the humming of bees. White regiments, black regiments, regulars and Rough Riders, representing the young manhood of the North and the South, fought shoulder to shoulder, unmindful of race or color, unmindful of whether commanded by ex-Confederate or not, and mindful of only their common duty as Americans.”

Pershing (left) with the commander of the Philippines Constabulary (right) and Moro chieftains in 1910 (Photo: Fort Huachuca Museum)

Pershing (left) with the commander of the Philippines Constabulary (right) and Moro chieftains in 1910 (Photo: Fort Huachuca Museum)After the war, Pershing was assigned to the Office of Customs and Insular Affairs, which oversaw the overseas territories the United States had taken Spain, including Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines and Guam.

In the Philippines, Pershing fought against both the Moros, an indigenous Muslim people who had previously fought for their independence from the Spanish, and a wider Filipino insurrection. Pershing studied Moro culture and dialects, read the Koran, and built relations with various Moro chiefs in an effort to win them over.

From 1903 to 1905, Pershing, now a Captain, attended the War College. After his graduation, he was given a diplomatic posting as military attaché to Tokyo, where he was an official observer in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05.

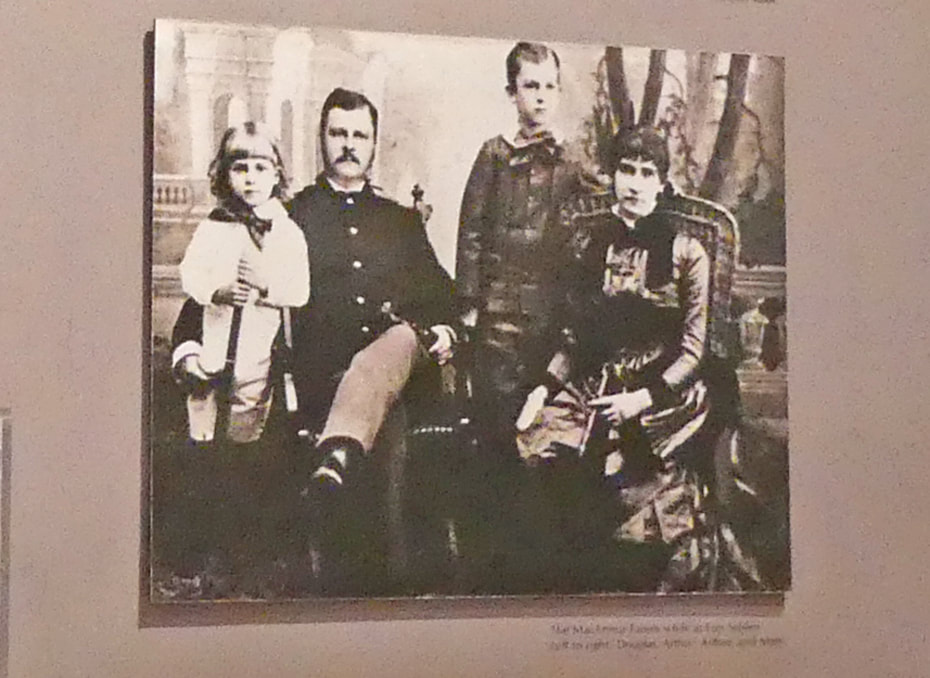

He met and married Helen Frances Warren, the daughter of Francis E. Warren, a powerful Republican Senator from Wyoming. They had four children: Helen, Ann, Warren, and Margaret. Pershing took his family with him when he returned to the Philippines for a few years, then later posted to San Francisco.

In 1906, President Roosevelt used his prerogative to promote Pershing to brigadier general. This was a controversial move, and many suggested that Pershing’s marriage had influenced the President. At the time, promotions were handed out based on seniority rather than merit, and Pershing had bypassed three ranks and skipped over 830 officers ahead of him. However, the President had the power to appoint general staff officers, but not lower-ranking ones and he chose to do this for the man he’d learned to respect in Cuba during the Spanish-American War.

Pershing’s San Francisco home after the fire, with the arrow indicating the window through which his son was rescued (Photo: National Park Service)

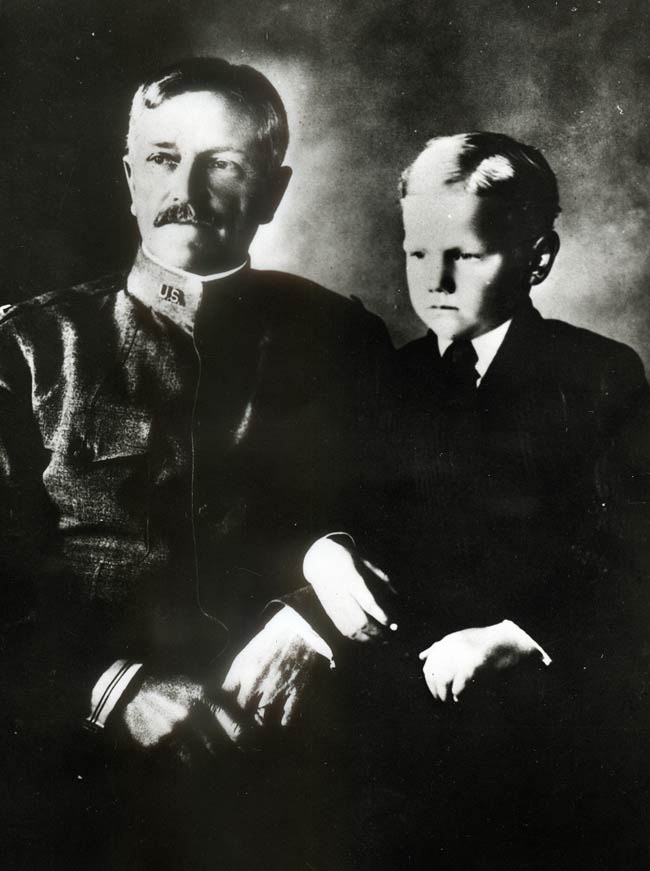

Pershing’s San Francisco home after the fire, with the arrow indicating the window through which his son was rescued (Photo: National Park Service)In 1915, personal tragedy struck when his home in San Francisco’s Presidio caught fire. Pershing’s wife and his three daughters were killed in the blaze, leaving him a widower with a five-year-old son named Warren. Pershing’s sister May took charge of the boy’s care and upbringing.

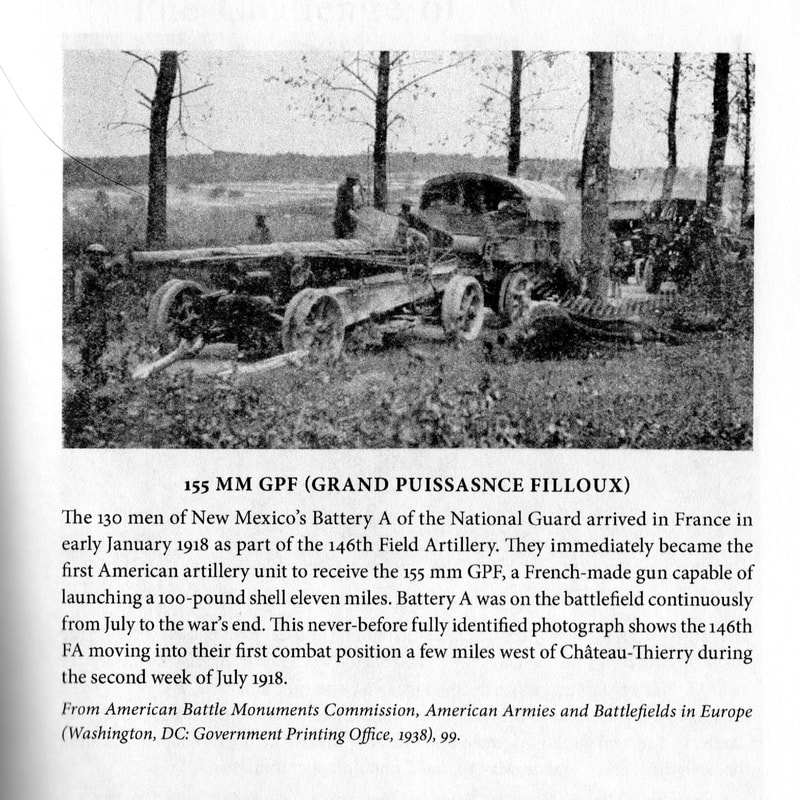

Pershing with his son Warren around the time of World War I. [Missouri Military Portraits, P1197-014515

Instead of taking time to grieve, Pershing leapt into action, leading 10,000 men on a punitive expedition into Mexico in an attempt to capture Pancho Villa, the bandit and revolutionary who had led several raids into U.S. territory, including the March 9, 1916 raid on Columbus, New Mexico. It was the first time the U.S. Army used mechanized vehicles in war. Cars, trucks, and airplanes were tested out in the deserts of Mexico and one of Pershing’s young officers, the future General George S. Patton, led the first motorized assault in U.S. military history, and killing Villa’s second-in-command. From the very start, the Punitive Expedition was doomed to failure. President Wilson, worried that a war might start, restricted the expeditions movements.

Pershing described the failed mission as

“a man looking for a needle in a hay stack with an armed guard standing over the stack forbidding you to look in the hay.”

Pershing (front, right) with Pancho Villa (center) half a year before the expedition, when Villa was still a friend to America. At the far right, George Patton looks over Pershing’s shoulder (Photo: University of Texas at Austin)

Soon after the Punitive Expedition returned to American soil, the United States entered World War I. President Woodrow Wilson had intended for General Frederick Funston to lead the expeditionary force into Europe. However, Funston died of a heart attack in February 1917, Pershing was selected to take his place. Again, Pershing received a promotion, this time jumping from major general to full, four-star general, skipping over the rank of lieutenant general.

Pershing arriving in Europe (Photo: gwpda.org)

Pershing arriving in Europe (Photo: gwpda.org)Pershing oversaw the organization, training and supply of the professional army, the draft army, and the National Guard, but he was unwilling to command under the kind of restraints that had plagued the Punitive Expedition. Before he would take command, Pershing made sure that will would give him unprecedented authority to run the AEF. In exchange, Pershing agreed not to meddle in political or national policy issues. This included Wilson’s racial policies, which kept the army segregated. Although Pershing had proved that he was willing to lead colored soldiers in battle, he could not in Europe. Pershing, who wanted to keep American troops under American command instead of allowing them to become reinforcements in British and French units, allowed two black divisions to be transferred to French leadership so that they would be allowed to see combat.

Buffalo Soldiers of the 92nd Division inspecting gas masks in France, 1918 (Photo: National Archives and Records Administration)

At the end of the war, Pershing pushed the Supreme War Council, to reject German requests for an armistice, and instead occupy Germany. He argued that German people might later feel they were never “properly” defeated and war would again break out. Woodrow Wilson, anxious to finish the war before the upcoming mid-term elections, and Britain and France, tired of war, disagreed and the armistice signed. During his own tenure as President, Franklin D. Roosevelt acknowledged that Pershing had been right.

One version of the Pershing Map (Photo: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers)

One version of the Pershing Map (Photo: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers)Pershing returned to the United States a hero. In 1919, Congress authorized President Wilson to promote him to the rank of General of the Armies of the United States, a rank that made him the second-highest paid government official after the President. It also allowed General Pershing to be on “active duty” for the rest of his life and continue to be available for assignments.

General Pershing served as Army Chief of Staff from 1921 to 1924. During this time, he created a map of a proposed national network of military and civilian highways, which became the foundation of the Interstate Highway System.

When the United States entered World War II, he served as a consultant. Many of his protégés, including George C. Marshall, Dwight Eisenhower, Omar Bradley, Leslie McNair, Douglas MacArthur and George S. Patton led troops. His memoir, My Experiences in World War, won the Pulitzer Prize for history in 1932.

After suffering a stroke, John Pershing died in his sleep on July 15, 1948. His body lay in state in the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol. An estimated 300,000 people came to see his funeral procession He was buried with honors in Arlington National Cemetery, at a site known as Pershing Hill. The graves of Americans whom he commanded in Europe surround his.

Jennifer Bohnhoff's novel A Blaze of Poppies tells the story of the Punitive Expedition and America's involvement in World War I from the point of view of two New Mexicans: a national guardsman and a female rancher. It is available in ebook and pa

Ernest Wrentmore

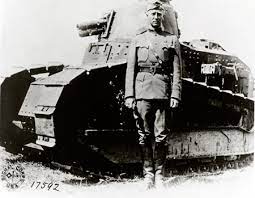

Ernest Wrentmore Pattonn in front of one of his tanks.

Pattonn in front of one of his tanks.