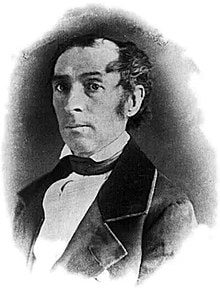

Pastel portrait of Manuel Armijo by Alfred S. Waugh, ca. 1840

Pastel portrait of Manuel Armijo by Alfred S. Waugh, ca. 1840Manuel Armijo was the last governor of New Mexico under the Mexican Republic, and the only person to serve in that office three times. Although he was dead by the time of the Civil War, he was important enough in New Mexican history that he still has an important role in Where Duty Calls, book 1 of a trilogy of middle grade historical novels set in New Mexico. In my attempt to present the historical controversy surrounding Armijo, the two main characters in my book have very different opinions of the man. One considers him a hero, while the other thinks him a villain. The truth, as is so often the case, is somewhere in between.

Manuel Armijo was born in Albuquerque in 1793. His father, Vicente Ferrer Armijo was a stockman and lieutenant in the militia. His mother was María Bárbara Chávez. The Armijo and Chavez clans were among the ricos of the Rio Abajo region and were among the wealthiest families in the region. The family home was in the Plaza de San Antonio de Belen. Manuel Armijo was already a landowner by the age of seventeen when there is a record of him selling a piece of land in Albuquerque.

Armijo began his public career in 1822, when he served as alcalde, a combination mayor and judge, in Albuquerque. During this period he protected his town by leading attacks against the Apache Indians, and was well respected for his administrative abilities. He was so well loved by the people that he was appointed governor in 1827.

While governor, Armijo sent reports to the central government expressing concern with poverty caused by the concentration of lands in the hands of a few people, and by drought. He asked for relief for New Mexicans who lived in poverty and hunger. Although his reports were ignored, his concern won him the appreciation of the people.

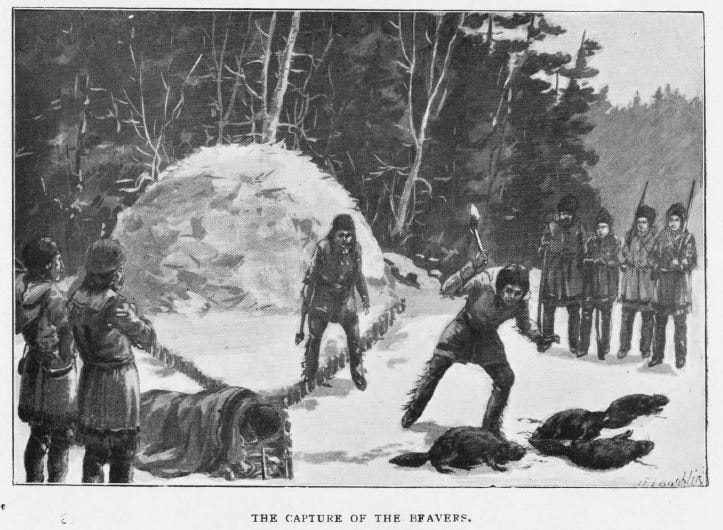

Armijo also expressed concern with illegal beaver trapping by Americans who were driving the animals to the point of extinction. He tried to impose tariffs and impound illegal furs, but the vast distances in the frontier made policing difficult. Unsurprisingly, his actions caused animosity with American traders and trappers, who retaliated by circulating rumors that the money gathered from tariffs and the resale of impounded furs lined Armijo’s pockets instead of helped New Mexico’s poor.

Armijo began his public career in 1822, when he served as alcalde, a combination mayor and judge, in Albuquerque. During this period he protected his town by leading attacks against the Apache Indians, and was well respected for his administrative abilities. He was so well loved by the people that he was appointed governor in 1827.

While governor, Armijo sent reports to the central government expressing concern with poverty caused by the concentration of lands in the hands of a few people, and by drought. He asked for relief for New Mexicans who lived in poverty and hunger. Although his reports were ignored, his concern won him the appreciation of the people.

Armijo also expressed concern with illegal beaver trapping by Americans who were driving the animals to the point of extinction. He tried to impose tariffs and impound illegal furs, but the vast distances in the frontier made policing difficult. Unsurprisingly, his actions caused animosity with American traders and trappers, who retaliated by circulating rumors that the money gathered from tariffs and the resale of impounded furs lined Armijo’s pockets instead of helped New Mexico’s poor.

Charles Beaubien

Charles BeaubienArmijo had returned to private business by 1837, when a rebellion broke out and the governor, a Mexican named Albino Perez, was murdered. Armijo led troops against the disorderly mob. He hung the four rebels responsible for starting the rebellion and executed the rebel-appointed governor.

When the Mexican government appointed Armijo to a second term as governor, Armijo imposed tariffs on American and New Mexican traders who brought goods over the Santa Fe Trail. He also distributed large land grants, ostensibly to draw in settlers from Mexico and the United States and widen the tax base. However, much of the money from those grants did not make it into New Mexico’s coffers. For instance, when Armijo granted Guadalupe Miranda and Charles Beaubien a large tract of land east of Taos along the Cimarron and Canadian Rivers in 1841, they deeded Armijo one-fourth interest in the land in exchange for his guarantees to support them against any future claims. They deeded another fourth to Charles Bent, who would later become Territorial Governor and be murdered by an angry mob for his alleged siphoning of money away from the people.

When the Mexican government appointed Armijo to a second term as governor, Armijo imposed tariffs on American and New Mexican traders who brought goods over the Santa Fe Trail. He also distributed large land grants, ostensibly to draw in settlers from Mexico and the United States and widen the tax base. However, much of the money from those grants did not make it into New Mexico’s coffers. For instance, when Armijo granted Guadalupe Miranda and Charles Beaubien a large tract of land east of Taos along the Cimarron and Canadian Rivers in 1841, they deeded Armijo one-fourth interest in the land in exchange for his guarantees to support them against any future claims. They deeded another fourth to Charles Bent, who would later become Territorial Governor and be murdered by an angry mob for his alleged siphoning of money away from the people.

While Armijo was making a bundle on land, the Republic of Texas was threatening to take it all away. Texas claimed that their western border followed the Rio Grande, effectively cutting New Mexico in half. In 1841, a group dubbed the Texas-Santa Fe expedition attempted to make good on that claim. When their guides abandoned them, the Texans got lost in the Llano Estacado, where they endured frequent attacks by Apaches. By the time the expedition finally arrived in New Mexico, they were half-starved and in no condition to battle Armijo, who had a large force of well-armed soldiers from Mexico, which was angry about losing Texas. The Texans surrendered and were marched 2,000 miles under harsh conditions to Mexico City. They languished in Perote prison until the United States negotiated their release a year and a half later.

New Mexicans considered Armijo a hero for defeating the Texans and for his support of the people. In an early scene, Raul Atencio, one of the main characters in Where Duty Calls, is walking past the cemetery in San Miguel Mission, where Armijo is buried, Raul nods as a way of paying respect. That day at the family meal, his uncle gleefully tells the story of the failed Texas-Santa Fe expedition, and paints Armijo as New Mexico’s greatest hero. For obvious reasons, Texans felt otherwise. The father of Jemmy Martin, another character was a part of the Texas-Santa Fe expedition, and paints a rather brutal picture of the treatment the Texans received, vilifying Armijo.

In March 1844 Governor Armijo resigned his office. The man who replaced him raised tariffs on imported goods and taxed the people even more. In order to avoid revolt, Armijo was re-appointed to his third and final term as governor by mid 1845.

New Mexicans considered Armijo a hero for defeating the Texans and for his support of the people. In an early scene, Raul Atencio, one of the main characters in Where Duty Calls, is walking past the cemetery in San Miguel Mission, where Armijo is buried, Raul nods as a way of paying respect. That day at the family meal, his uncle gleefully tells the story of the failed Texas-Santa Fe expedition, and paints Armijo as New Mexico’s greatest hero. For obvious reasons, Texans felt otherwise. The father of Jemmy Martin, another character was a part of the Texas-Santa Fe expedition, and paints a rather brutal picture of the treatment the Texans received, vilifying Armijo.

In March 1844 Governor Armijo resigned his office. The man who replaced him raised tariffs on imported goods and taxed the people even more. In order to avoid revolt, Armijo was re-appointed to his third and final term as governor by mid 1845.

When the Mexican-American War began in May 1846, hundreds of enthusiastic but ill-equipped, ill-trained citizens answered Armijo’s call to arms against the American invasion. Although many of his volunteers were armed with nothing more than pitchforks and machetes, Armijo sent them to fortify Apache Canyon, a narrow space on the Santa Fe trail, just east of Santa Fe. By this time Armijo has grown so fat that a horse could not support his weight. The rotund general arrived on the battlefield astride a strong-backed mule, Armijo found his men lined up against General Stephen Kearny and his 1,750 well armed and well-trained soldiers. Armijo abandoned his forces. Some accounts say he even abandoned his own wife. What he didn’t abandon were the fine carpets, silver and china of the Governor’s Palace, which were loaded into carts. He, his treasures, and his bodyguard of 75 dragoons retreated to Chihuahua, Mexico, allowing General Kearny to take Santa Fe without a battle.

San Miguel Church, Socorro Illustration by Ian Bristow in Where Duty Calls

San Miguel Church, Socorro Illustration by Ian Bristow in Where Duty CallsWhen asked why he abandoned New Mexico, Armijo justified himself by saying “I had but seventy-five men to fight three thousand. What could I do?” American writers, in their negative depiction of Armijo, have suggested that he accepted a bribe from the Americans for not opposing Kearny, but there is no concrete evidence to support this assertion. Armijo was tried for treason, but neither the Mexican Supreme Court or Congress found enough evidence to convict him. In January 1850 Armijo returned as a hero to New Mexico. He died at his home in Lemitar, New Mexico in January 1854 and was given a hero’s burial in San Miguel Mission Church in Socorro..

Jennifer Bohnhoff taught New Mexico history to 7th graders in Albuquerque and Edgewood, New Mexico. A native New Mexican, she is the author of several novels for middle grade and adult readers. Where Duty Calls will be published by Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesia Publishing in June 2022 and is currently available for preorder as both a paperback

No comments:

Post a Comment