From The Civil War in Texas and New Mexico, by Steve Cotrell.

From The Civil War in Texas and New Mexico, by Steve Cotrell.In 1861, Confederate Brigadier General Henry Sibley led his Army of New Mexico, 3 regiments of Texas Mounted Volunteers, into New Mexico Territory. It was the first step in his plan to capture the entire southwest, including the Colorado goldfields and California’s deep-water ports. But things didn’t go as planned. Instead of taking the territory for the Confederacy, the campaign was an unmitigated disaster. Sibley’s starved soldiers retreated back to Texas, littering the desert and mountains with debris that souvenir hunters are still uncovering. Of the original 2,500-man brigade, only 1,500 made it back to San Antonio by the fall of 1862.

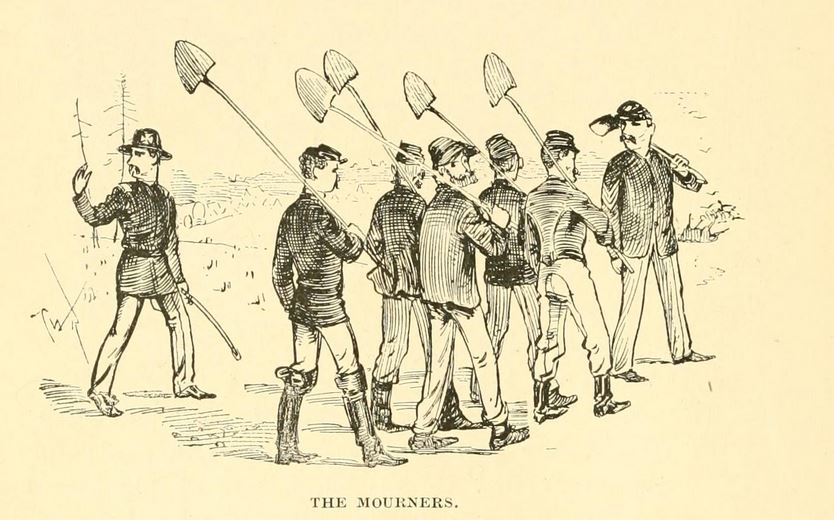

From Where Duty Calls. Illustration by Ian Bristow

From Where Duty Calls. Illustration by Ian BristowLike elsewhere in the Civil War, disease took more of Sibley’s soldiers than battle did. Altogether, two-thirds of the approximately 660,000 deaths of soldiers in the Civil War were caused by uncontrolled infectious diseases. Although malaria, common in the south, was less prominent in the dry desert, pneumonia, typhoid, diarrhea and dysentery were common among his troops. Sibley’s men were burying the dead before they even crossed the border into Union territory.

Jemmy. Ian Bristow, illustrator

Jemmy. Ian Bristow, illustratorJemmy Martin, a young Texan in my historical novel, Where Duty Calls, is not a soldier, but a packer, in charge of making sure the army’s supplies are loaded into his wagon correctly. Jemmy has a big heart that breaks every time he sees an animal or person die. He is particularly affected when William Kemp dies. On Jemmy’s first day in Sibley’s camp, William had cut his own bar of soap in two so that Jemmy would have some. When William dies of pneumonia, Jemmy is overcome with sorrow and guilt. While Jemmy is fictitious, William Kemp is not. Official Confederate records show that a private William Kemp died of pneumonia on February 12, 1862. He was buried at the side of the trail somewhere south of Fort Craig, New Mexico. His grave was unmarked and has never been found or identified.

In Where Duty Calls, Jemmy breaks apart wooden food crates to build William’s coffin. Although he wants to carefully pull out the nails so he can reuse both the wood and the nails, his grief gets the better of him. In his frustration, Jemmy pounds the nails so hard that he bends them and splits the wood.

Just as William Kemp is based on a real person, the idea of making a coffin from food crates is not a figment of my imagination. Wood was a rare and precious commodity in New Mexico Territory. Burying every dead person in a coffin would be a terrible waste in the desert, where wood was needed for fires to cook food and keep the troops warm. In I Married A Soldier, a memoir of Army life in the Southwest during the 1850s-1870s, Lydia Spencer Lane explains that wood was so scarce that it was customary for those who lived in New Mexico to not bury their dead in coffins. She explains that in Santa Fe, the dead were carried to church in a coffin, but before burial the body was removed and rolled in old blankets. Thus, coffins could be used and reused indefinitely.

A Box of Hardtack. From Hardtack and Coffee by John D. Billings

A Box of Hardtack. From Hardtack and Coffee by John D. BillingsHowever, Ms. Lane elaborates that the practice of burying the dead without a coffin was not acceptable to people who had been raised in the East, who did everything within their power to create coffins for their dead. When there was not enough lumber at hand to make a coffin, she explains, packing boxes and commissary boxes were used. She relates the story of one officer who died at a post in Texas and was carried to his final resting place in a very rough coffin which had marked, in great black letters along the side, "200 lbs. bacon."

From Where Duty Calls. Illustrated by Ian Bristow

From Where Duty Calls. Illustrated by Ian BristowIn Where Duty Calls, when the grave is deep enough and the coffin complete, the entire troop follows Willie the drummer boy out of camp as he drums a funeral march. They lower William Kemp’s coffin into the hole, then sing When I can read my title clear. Written by Isaac Watts, an English Congregational minister, hymn writer, theologian, and logician who lived between 1674 and 1748, it was very popular at the time of the Civil War. Other hymn written by Watts, among them When I Survey the Wondrous Cross, Joy to the World, and Our God, Our Help in Ages Past have better endured the passing of time.

When I can read my title clear

to mansions in the skies,

I bid farewell to every fear,

and wipe my weeping eyes.

Let cares, like a wild deluge come,

and storms of sorrow fall!

May I but safely reach my home,

my God, my heav’n, my All.

Jennifer Bohnhoff, a former high school and middle school history teacher, is the author of several middle grade historical fiction novels. Where Duty Calls is the first in a trilogy of novels set in New Mexico during the Civil War and is published by Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesi

No comments:

Post a Comment