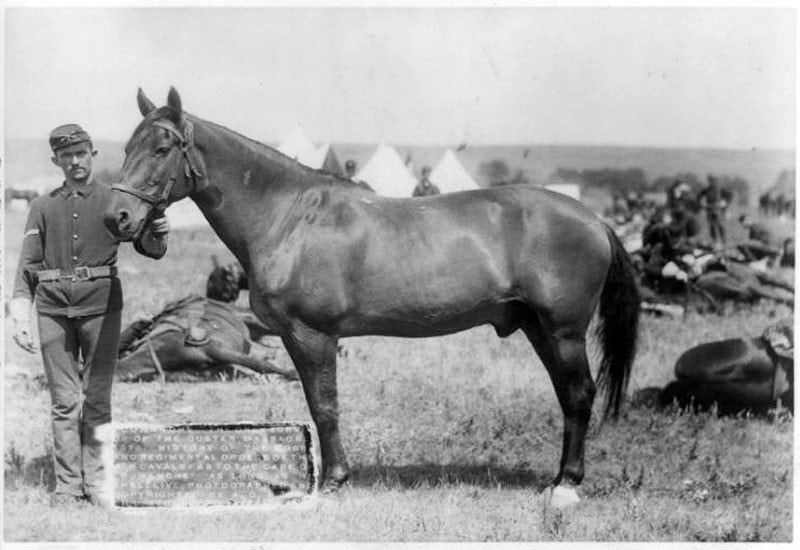

The anniversary of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, which Plains Indians call the Battle of the Greasy Grass and is often called Custer's Last Stand, happened last week. The battle, which took place on June 25-26, 1876 along the Little Bighorn River in southeastern Montana Territory, was an overwhelming victory for the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho. The 7th Cavalry troops engaged in this battle were all killed. The only survivor was a buckskin gelding named Comanche.

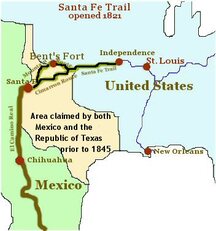

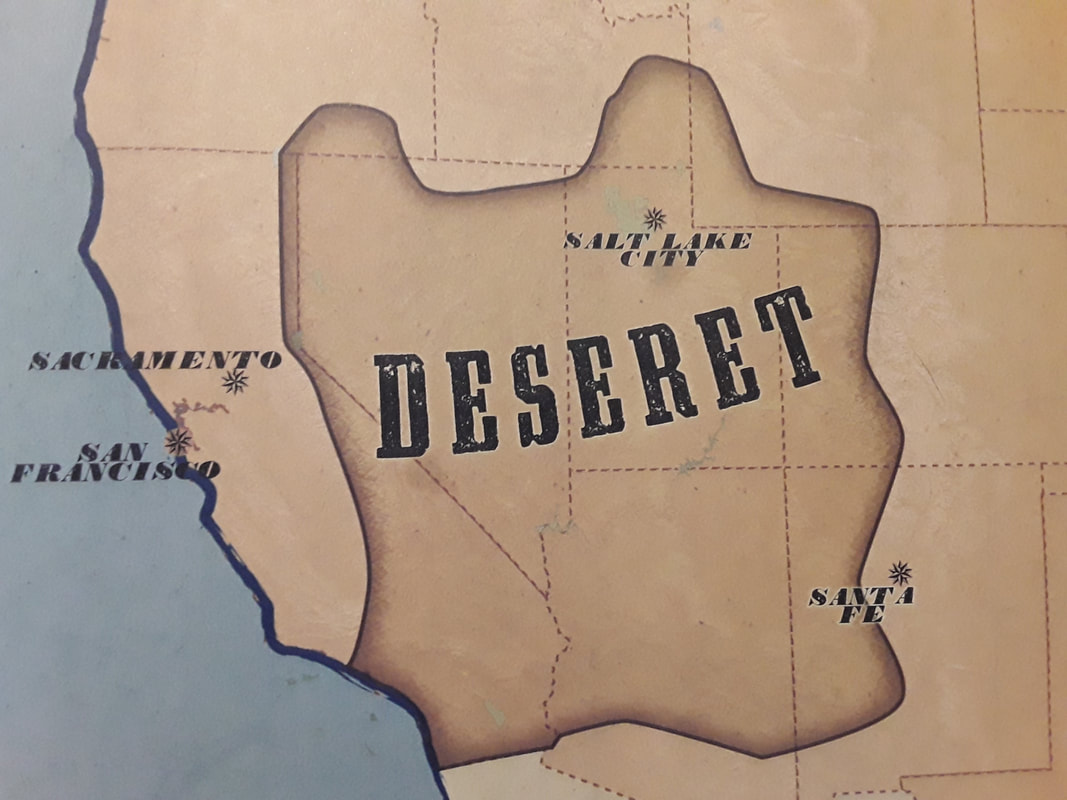

Comanche was born around 1862 on the flat plains that were then called the Great Horse Desert of Texas. Like the thousands of mustangs that roamed the region, he exhibited the black stripe down his back and dun coloration of the early Spanish horses from which they were descended. Comanche had a small white star on his forehead and stood 15 hands tall. Many noted that his big head, thick neck, and short legs were out of proportion for his body. But what he lacked in beauty, he made up for in bravery.

Comanche was born around 1862 on the flat plains that were then called the Great Horse Desert of Texas. Like the thousands of mustangs that roamed the region, he exhibited the black stripe down his back and dun coloration of the early Spanish horses from which they were descended. Comanche had a small white star on his forehead and stood 15 hands tall. Many noted that his big head, thick neck, and short legs were out of proportion for his body. But what he lacked in beauty, he made up for in bravery.

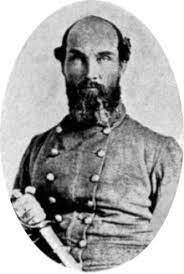

Myles Keogh, 1872

Myles Keogh, 1872Comanche was captured in a wild horse muster on April 3, 1868. The army bought him for $90, which was an average price for an upbroken mustang. He was loaded into a railroad car and shipped to Fort Leavenworth, where he and the other horses were branded. First Lieutenant Tom W. Custer, the brother of Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer bought him and 40 other horses for use by the 7th cavalry.

Captain Myles Keogh of the 7th Cavalry’s I Company liked the look of Comanche and bought him for his own personal mount. In September 1868, while fighting the Comanche in Kansas, the horse was wounded by an arrow in the hindquarters but continued to let Keogh fight from his back. Keogh named his mount “Comanche” after that engagement as a tribute to the horse’s bravery. Comanche was wounded many more times and always exhibited the same toughness that he did in his first battle.

Captain Myles Keogh of the 7th Cavalry’s I Company liked the look of Comanche and bought him for his own personal mount. In September 1868, while fighting the Comanche in Kansas, the horse was wounded by an arrow in the hindquarters but continued to let Keogh fight from his back. Keogh named his mount “Comanche” after that engagement as a tribute to the horse’s bravery. Comanche was wounded many more times and always exhibited the same toughness that he did in his first battle.

Myles Keogh grave site, 1879.

Myles Keogh grave site, 1879.On June 25, 1876, Captain Keogh rode Comanche into what became known as the Battle of Little Bighorn. When other soldiers arrived at the battlefield two days later, they found that all of the men riding with Custer that day had been killed. Perhaps as many as a hundred of the 7th Cavalry’s horses had survived the battle and were taken by Indian warriors. A yellow bulldog tht had been with the troops was missing, too. Comanche had been left behind, the only living thing left on the battlefield, Even though he wasn't, Comanche became known as the lone survivor of the Battle of Little Bighorn.

It is supposed that the reason Comanche was left behind is that he was close to death and the Indians assumed he wouldn’t make it. Comanche had had arrows sticking out of him and had lost a lot of blood. Four bullets had punctured the back of the shoulder, another had gone through a hoof, and he had one gunshot wound on either hind leg. His coat was matted with dried blood and soil.

It is supposed that the reason Comanche was left behind is that he was close to death and the Indians assumed he wouldn’t make it. Comanche had had arrows sticking out of him and had lost a lot of blood. Four bullets had punctured the back of the shoulder, another had gone through a hoof, and he had one gunshot wound on either hind leg. His coat was matted with dried blood and soil.

Sergeant John Rivers, the 7th Cavalry’s farrier , and an old battle comrade of Myles Keogh, inspected Comanche and decided that he would survive. While the solders were busy burying their 7th Calvary comrades, Rivers took charge of the animal. Comanche was sent Fort Meade, in what is now the Sturgis, South Dakota, where he recovered from his wounds under veterinary care. A year later, he was shipped to Fort Riley, Kansas, where he became the 7th Cavalry’s mascot. Colonel Samuel D. Sturgis, the commanding officer, issued “General Order Number 7," which decreed that the horse would never again be ridden, and that he would always be paraded, draped in black, in all military ceremonies involving the 7th Cavalry.

“The horse known as ‘Comanche” being the only living representative of the bloody tragedy of the Little Big Horn, June 25th, 1876, his kind treatment and comfort shall be a matter of special pride and solicitude on the part of every member of the Seventh Cavalry to the end that his life be preserved to the utmost limit..."

"Further, Company I will see that a special and comfortable stable is fitted for him and he will not be ridden by any person whatsoever, under any circumstances, nor will be put to any kind of work.”

"Further, Company I will see that a special and comfortable stable is fitted for him and he will not be ridden by any person whatsoever, under any circumstances, nor will be put to any kind of work.”

Comanche was given the honorary title of a “Second Commanding Officer” of the 7th Cavalry. He was even “interviewed” for the daily papers when Sergeant Rivers told his story.

In 1891, Comanche died of colic, a common ailment of old horses. He was likely 29 years old. He is one of only three horses who have been given a full military funeral. The only other horses so honored were Black Jack, who served in more than a thousand military funerals in the 1950s and 1960s, and Sergeant Reckless, who served in Korea.

In 1891, Comanche died of colic, a common ailment of old horses. He was likely 29 years old. He is one of only three horses who have been given a full military funeral. The only other horses so honored were Black Jack, who served in more than a thousand military funerals in the 1950s and 1960s, and Sergeant Reckless, who served in Korea.

Comanche’s hide was stretched over a frame by Kansas taxidermist Lewis Dyche and remains on exhibit in the University of Kansas’ Natural History Museum, in Dyche Hall.

A retired Middle School History and Language Arts teacher, Jennifer Bohnhoff writes historical fiction and contemporary novels for older children and adults. You can read more about her and her books on her blog.