At the beginning of the Civil War, Henry Hopkins Sibley had a grandiose plan. Because he'd been stationed at Fernando de Taos and at Fort Union, he thought he knew the territory of New Mexico. But he didn't know it well enough, and his grandiose plan failed. He later blamed his failure not on his incompetence or lack of knowledge, but on the land itself.

When the Civil War broke out, Sibley was serving under the commander of the department, Colonel William W. Loring, a career Army officer who'd lost an arm during the Mexican American War. Loring, whose home state was Florida, had already sent his own letter of resignation to Washington when Sibley, a Louisiana native, tendered his resignation to him an April 28th.

Impatient to leave because of circulating rumors of high-ranking commissions in the Confederate Army, Sibley asked for “the authority to leave this Dept. immediately.”

When May 31 arrived and he still had not heard anything, he took seven days’ leave of absence, bid his command goodbye, and left Fort Union on the next stage. He accepted an appointment to colonel in the Confederate army. By June, 1861, Sibley had been promoted to brigadier general.

Impatient to leave because of circulating rumors of high-ranking commissions in the Confederate Army, Sibley asked for “the authority to leave this Dept. immediately.”

When May 31 arrived and he still had not heard anything, he took seven days’ leave of absence, bid his command goodbye, and left Fort Union on the next stage. He accepted an appointment to colonel in the Confederate army. By June, 1861, Sibley had been promoted to brigadier general.

Sibley's promotion was prompted by his visit to Richmond, Virginia, where he persuaded Confederate President Jefferson Davis that he could sweep through New Mexico and seize Colorado and California for the Confederacy.This bold plan would not only increase the size of the Confederacy, but it would achieve the dream of Manifest Destiny, making the rebel nation stretch from sea to shining sea. Gold from Colorado and California's gold fields would enrich the Southern war chest, and the deep water port of Los Angeles would help supply the army with materiel that was not getting through the Atlantic Union blockade. The proposal sounded too good to be true, especially since Sibley claimed he could do it without encumbering the Confederacy for his supplies. Sibley claimed that he could live off the land during his trek through New Mexico. He believed there was enough water, fodder for the animals, and food for his men. He had heard enough New Mexicans complain about the army presence that he believed New Mexicans would willingly support a Confederate army. Sibley was wrong, both about the amount of supplies available and about the people's opinion of the Confederate army that he led.

Brig. Gen. Henry H. Sibley's supply problems began long before he entered New Mexico Territory. Sibley began assembling his small army in San Antonio late in the summer of 1861. He quickly discovered that outfitting his troops would take far longer than he had anticipated. There were few available weapons, uniforms and military supplies for his 2,500 man force, which he had named The Army of New Mexico, and so when the men finally began the trek to the territories, many did so wearing their civilian clothing and carrying whatever weapons they had brought from home. This included squirrel guns, shotguns, and ancient blunderbusses.

One of the reasons Brig. Gen. Henry H. Sibley was so wrong about New Mexico's ability to sustain his army was a matter of timing. Since outfitting and training his troops took far longer than expected, Sibley's force didn’t begin the 600-mile march across Texas until November. The landscape of West Texas provided very little grass and other forage for the Army's horses and mules, and there was so little water that Sibley's line of march spaced itself so that each regiment was a full day behind the next, allowing the springs to recover somewhat between regiments. Still, the going was rough and the army began losing hoof stock.

After the war, William Lott Davidson, a 24-year old private in Company A of the 5th Texas, recalled that “‘Chill November’s surly blast’ came down upon us as we camped upon the Nueces. There was no timber to shield us and the wind swept at us, and the boys on guard at night must have had a hard time pacing their beats on the cold frozen ground. We were tasting the bitter delights and mournful realities of a soldier’s life. We are now for the first time beginning to find out that we are engaged in no child’s play.”

One of the reasons Brig. Gen. Henry H. Sibley was so wrong about New Mexico's ability to sustain his army was a matter of timing. Since outfitting and training his troops took far longer than expected, Sibley's force didn’t begin the 600-mile march across Texas until November. The landscape of West Texas provided very little grass and other forage for the Army's horses and mules, and there was so little water that Sibley's line of march spaced itself so that each regiment was a full day behind the next, allowing the springs to recover somewhat between regiments. Still, the going was rough and the army began losing hoof stock.

After the war, William Lott Davidson, a 24-year old private in Company A of the 5th Texas, recalled that “‘Chill November’s surly blast’ came down upon us as we camped upon the Nueces. There was no timber to shield us and the wind swept at us, and the boys on guard at night must have had a hard time pacing their beats on the cold frozen ground. We were tasting the bitter delights and mournful realities of a soldier’s life. We are now for the first time beginning to find out that we are engaged in no child’s play.”

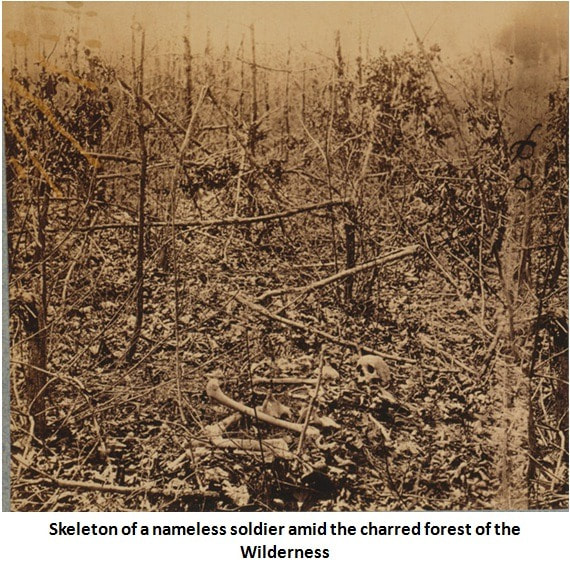

Nothing became easier after The Army of New Mexico entered New Mexico Territory. The weather at New Mexico's higher elevations was brutal. Firsthand accounts recall repeatedly waking up covered in snow. Davidson wrote that the sentries "paced in rags and tatters, their weary best through the long tedious hours of the night, with bare-feet over the frozen and ice-covered ground. ‘Found dead on post’ and ‘froze to death last night’ were sounds we often heard, as a poor, stiff, lifeless body was brought into camp, the dauntless spirit having gone to sleep, to rest with the brave.”

Blizzards, combined with too little food and forage led to illness among both men and beast. Measles and pneumonia ran rampant through the troops.

Blizzards, combined with too little food and forage led to illness among both men and beast. Measles and pneumonia ran rampant through the troops.

map by Matt Bohnhoff, from Where Duty Calls

map by Matt Bohnhoff, from Where Duty CallsAfter failing to take Fort Craig in a frontal assault, Sibley decided to execute what he called "a roundance on Yankeedom" and bypass the fort. This flanking march forced the Confederate Army away from the Rio Grande, the only source of water in the area. Both the men and their animals suffered intense thirst. Private Laughter of the 2nd Texas recalled that “The dry beef we had for supper needed moisture. The fact was, if one of us coughed you could see the dust fly.”

The old western saying that “whiskey is for drinking, but water is for fighting” proved true. The Battle of Valverde occured when the Confederate Army finally returned to the river on the other side of Contadora Mesa and found their access to water blocked by Union troops.

The old western saying that “whiskey is for drinking, but water is for fighting” proved true. The Battle of Valverde occured when the Confederate Army finally returned to the river on the other side of Contadora Mesa and found their access to water blocked by Union troops.

To add to the misery, a major sandstorm, one of many recorded in soldier's diaries and memoirs, hit just before the battle of Valverde. These brutal storms were more proof that Sibley's men were campaigning in the extreme and inhospitable environment of the upper Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts.

illustration by Ian Bristow in The Worst Enemy

illustration by Ian Bristow in The Worst EnemyThe Confederate's problems continued as the Army continued to head north. In Albuquerque, where they had hoped to pillage the government storehouses. They found that the Union soldiers had burned the supplies before retreating north. Running low on everything, Sibley was once again forced to split his forces in order to maximize their ability to forage on the sparse winter grass. Private Davidson was part of the army that was sent into the Sandia Mountains, where it was believed that grass was abundant. He found that what grass there was was buried beneath deep snow. "The army was marched out in the mountains east of Albuquerque and camped, as I thought, for the winter as the weather was very cold, sleeting and snowing all the time. At this camp we remained a week and we buried fifty men, and if the weather and exposure had continued much longer, we would have buried the whole brigade.”

The weather was no kinder in the mountains east of Santa Fe, where the Santa Fe Trail snaked through Glorieta Pass on its way to Fort Union, where the Confederate Army hoped to capture a wealth of Union supplies. The Texans won another tactical victory at the Battle of Glorieta, but returned to their supply train to find it burned. That night, Davidson wrote that “a severe snow storm arose and snow fell to the depth of a foot and several of our wounded froze to death.”

The weather was no kinder in the mountains east of Santa Fe, where the Santa Fe Trail snaked through Glorieta Pass on its way to Fort Union, where the Confederate Army hoped to capture a wealth of Union supplies. The Texans won another tactical victory at the Battle of Glorieta, but returned to their supply train to find it burned. That night, Davidson wrote that “a severe snow storm arose and snow fell to the depth of a foot and several of our wounded froze to death.”

illustration by Ian Bristow in The Famished Country

illustration by Ian Bristow in The Famished CountryWeakened by two battles, long marches, extended exposure, repeated winter storms, and insufficient supplies, it became clear that the Confederate Army had no choice but to to withdraw back down the Rio Grande. With the exception of a couple of cannonade skirmishes at Albuquerque and Peralta, Colonel Canby, the cautious commander of Union forces in New Mexico was content to not engage in any more battles. Instead, he allowed the weather and terrain to finish off Sibley’s army while he skirted alongside the Rio Grande, herding the pitiful remnants of The Army of New Mexico out of the territory they'd hoped to conquer.

map by Matt Bohnhoff, included in The Famished Country

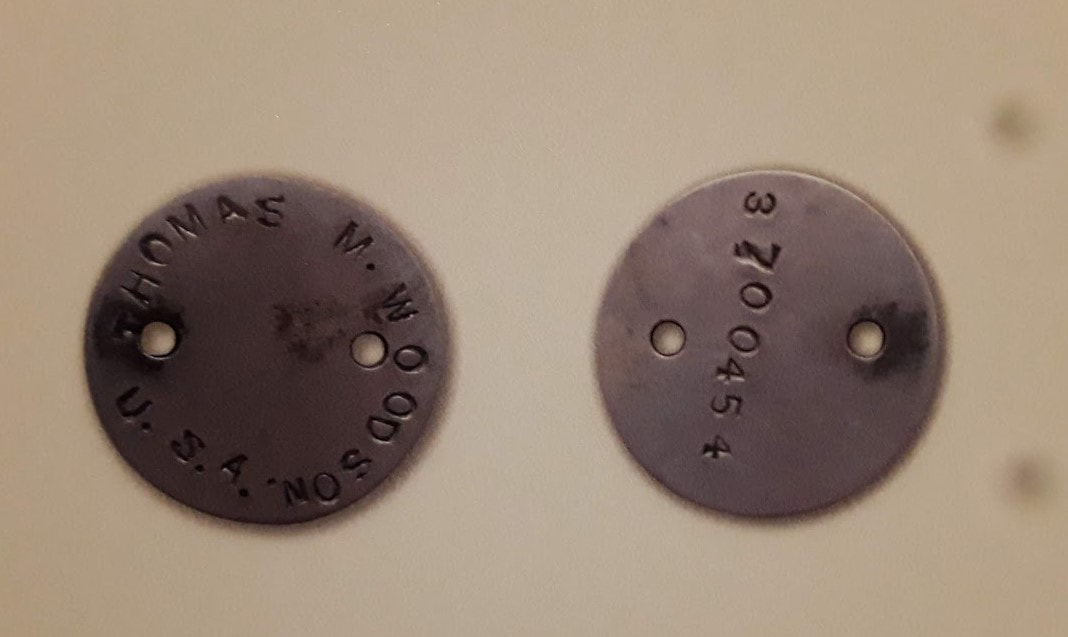

map by Matt Bohnhoff, included in The Famished CountryBrig. Gen. Henry H. Sibley had launched an invasion force of 2,500 men in a grandiose scheme to take the Colorado and California goldfields, establish a port on the Pacific coast, and open a route for a coast to coast railroad system, all of which would have dramatically expanded the Confederacy’s presence in the Southwest and perhaps changed the trajectory of the war. By the time his disastrous retreat was completed in the summer of 1862, he returned to San Antonio with less than a third of the men he had begun with. Davidson wrote that, “We left San Antonio eight months earlier with near three thousand men ….And now in rags and tatters, foot-sore and weary, we again march, if a reel and stagger can be called a march, along the streets of San Antonio with fourteen hundred men. I can furnish a list of four hundred and thirty-seven dead, but where are the other sixteen hundred?” While not all the the unrecorded can be accounted for, many deserted on the long retreat, heading for California or hiding in the hills.

In a letter to John McRae, the father of Alexander McRae, a native South Carolinian who fought for the Union, General Sibley blamed the countryside itself for his retreat.

In a letter to John McRae, the father of Alexander McRae, a native South Carolinian who fought for the Union, General Sibley blamed the countryside itself for his retreat.

“You will naturally speculate upon

the causes of my precipitate evacuation

of the Territory of New Mexico

after it had been virtually conquered.

My dear Sir, we beat the enemy

whenever we encountered him.

The famished country beat us.”

Sibley's New Mexico Campaign was small in comparison to the battles waged in the east. But on a percentage basis, it was one of the most devastating campaigns any Civil War army suffered through without surrendering. That outcome is even more dramatic when we consider the fact that each of the engagements was a tactical victory for the Confederate forces. Ultimately, Sibley was driven back, far short of his ambitious goals, by the sparsely populated territory's brutal terrain and unforgiving distances. It was, indeed, the famished country that beat him.

The Famished Country, a phrase taken from Major Sibley's letter to John McRae, is the title of Book 3 of Rebels Along the Rio Grande, a trilogy of historical fiction novels for middle grade through adult readers. Published by Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesia Publishing, The Famished Country will be available in October, 2024.