Photo credit: author. Taken inside the American Cemetery new Belleau Woods.

Photo credit: author. Taken inside the American Cemetery new Belleau Woods.When I visited American World War I cemeteries in Europe in 2019, one of the most sobering things to see were the graves to unmarked soldiers. Historically, most soldiers who died in battle were never identified. The Graves Registration Service, called Mortuary Affairs" since 1991, has changed that. This organization is charged with making sure that fallen American soldiers are identified and are laid to rest in proper burial places.

From ancient times, rank-and-file soldiers were usually stripped of arms and armor and left on the battlefield for human and animal scavengers. In later centuries, a swift burial near the place of death became the norm. Only in the case of the famous or the high ranking was an effort made to identify the deceased. In remote American frontier outposts, quartermasters buried dead soldiers, often without a coffin since wood was in short supply. They marked the graves with whatever they had on hand, and entered the death into the records. Forts moved, grave markers fell down or rotted away, and the location of the graves were lost to time.

Things hadn’t changed much by the time the United States invaded Mexico during the 1846-47 Mexican-American War. When the U.S. government wanted to build a monument to the men who died in the Battle of Buena Vista, they could not find where General Zachary Taylor, who later became our 12th President, had buried his fallen men because he did not mark the location on the map in his report.

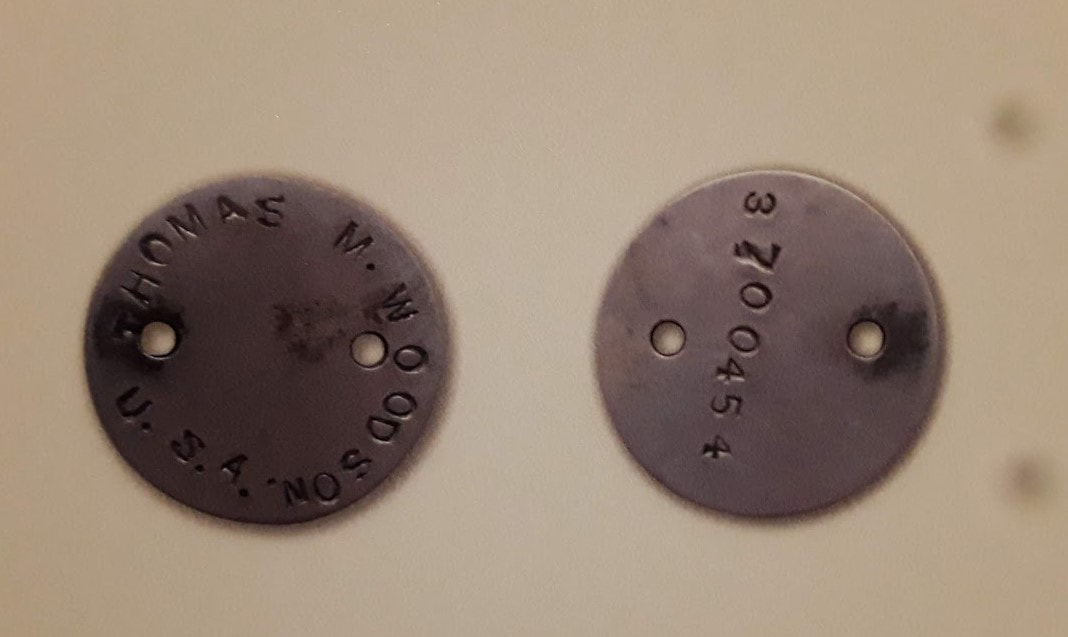

During the American Civil War, soldiers themselves began to take their identification should they die in battle into their own hands. Although there was no officially mandated form of identification, soldiers often pinned paper slips on their coats with their name and address. Others bought commercially made badges with their name and unit engraved.

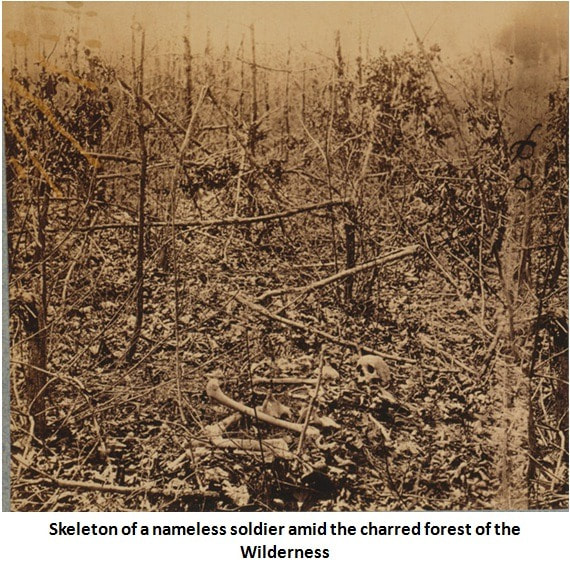

When the Union Army of the Potomac crossed the Rapidan River and entered Virginia on May 4, 1864, they were appalled to find the bones of their former comrades, lost a year earlier, lying unattended on the ground. Many soldiers examined the remains for markings on clothing or equipment, the nature of the fatal wound, and dental peculiarities such as missing teeth in an attempt to identify the fallen. This approach became the centerpiece of 20th century identification methods. Once done, the men buried the deceased before moving on.

Captain James M. Moore of the Quartermaster Cemeterial Division personally led a group of his men to the field after the Battle of Fort Stevens outside Washington, D.C. They searched for and recovered both remains and personal items, identifying every single Union soldier lost in that battle. This effort helped establish the Quartermaster Corps as the entity in charge of caring for the fallen.

Captain James M. Moore of the Quartermaster Cemeterial Division personally led a group of his men to the field after the Battle of Fort Stevens outside Washington, D.C. They searched for and recovered both remains and personal items, identifying every single Union soldier lost in that battle. This effort helped establish the Quartermaster Corps as the entity in charge of caring for the fallen.

By war’s end, Congress had authorized a national cemetery system and the remains of Union soldiers were disinterred and reburied at them. One of those cemeteries was created through the efforts of John P. Slough, the Union Commander at the Battle of Glorieta Pass. After the war he returned to New Mexico to serve as the territory’s Chief Justice and during that time he helped create the Veteran’s cemetery in Santa Fe to inter the Union soldiers who had died while serving under him. Later, Confederate soldiers were reinterred there as well. Nation wide, some 300,000 dead soldiers were moved from their temporary graves to the newly established national cemeteries.

During the Spanish-American War, the U.S. became the first country to institute the policy that soldiers killed abroad should be returned to their next-of-kin. In the Philippines, Chaplain Charles C. Pierce established the QM Office of Identification and started developing what have become the modern identification techniques. He collected information such as place of death, the nature of the wounds, and the physical characteristics of the deceased soldiers, resulting in unprecedented accuracy even with bodies weeks or months old. He also suggested that a soldier's combat field kit should contain an "identity disk," the forerunner of the "dog tag" that American soldiers began wearing in 1917, when America entered World War I.

General John (Black Jack) Pershing, the leader of the American Expeditionary Force in World War I, recalled the now-retired Major Pierce into service to head the newly created Graves Registration Service (GRREG) so that the 47,000 U.S. servicemen who would die in Europe could be found, identified and returned home.

Pershing noted the courage of these men in recovering the bodies of their comrades in 1918:

Pershing noted the courage of these men in recovering the bodies of their comrades in 1918:

"(They) began their work under heavy shell of fire and gas, and, although troops were in dugouts, these men immediately went to the cemetery and in order to preserve records and locations, repaired and erected new crosses as fast as old ones were blown down. They also completed the extension to the cemetery, this work occupying a period of one and a half hours, during which time shells were falling continuously and they were subjected to mustard gas. They gathered many bodies which had been first in the hands of the Germans, and were later retaken by American counterattacks. Identification was especially difficult, all papers and tags having been removed, and most of the bodies being in a terrible condition and beyond recognition.”

While some of the dead were disinterred from temporary cemeteries and returned to the U.S. after the war, 30,000 were left in permanent cemeteries in Europe. Like former President Theodore Roosevelt, who requested that his son, Quentin, be buried near the site where his plane crashed, many believed that soldiers killed overseas should remain there.

The GRREG was disbanded after World War I and had to be reactivated in World War II, when 30 GRREG companies worked in perilous conditions. Famous war correspondent Ernie Pyle reported that the men recovering the dead during the heavy fighting at Anzio frequently had to take shelter in freshly dug graves. They also had to deal with dangers such as booby-trapped bodies and snipers. When collecting bodies and taking them to temporary burial sites, the GREGG tried to use a route that avoided combat troops so the latter wouldn't have to be confronted with the death of their comrades. The grisly work resulted in some of the highest rates of PTSD in the military.

During the Korean War in 1950, the chaotic nature of the front, the mountainous terrain, and the uncertain lines of communication prevented the establishment of large cemeteries. The 108th QM Graves Registration Platoon, the only grave registration unit in Korea, sent 15 men to each of the three U.S. divisions to help in the construction of individual division cemeteries, which ended up being dug up so they wouldn't fall into enemy hands. The policy of "concurrent return, sending the fallen to the U.S. without first going into a temporary cemetery, which is still in effect today, grew out of that turmoil.

By the time of the Vietnam War, the identification of war dead had improved greatly, aided by ever-improving transportation, communication and laboratories. Only 28 American soldiers killed during the Vietnam War remained unidentified by the war's end. Using DNA analysis, the last one was identified in 1998.

May it be that no future comrade in arms will ever have to remain "known but to God."

By the time of the Vietnam War, the identification of war dead had improved greatly, aided by ever-improving transportation, communication and laboratories. Only 28 American soldiers killed during the Vietnam War remained unidentified by the war's end. Using DNA analysis, the last one was identified in 1998.

May it be that no future comrade in arms will ever have to remain "known but to God."

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a former educator who writes historical fiction for middle grade readers through adults. You may read more about her and her books here, on her website.

No comments:

Post a Comment