In his day, the handsome and charming Rupert Brooke was a celebrity. In Dictionary of Literary Biography, Doris L. Eder calls him "a golden-haired, blue-eyed English Adonis." The Irish poet W B. Yeats called him “the most handsome man in Britain". But it was his poetry that made Brooke a national hero.

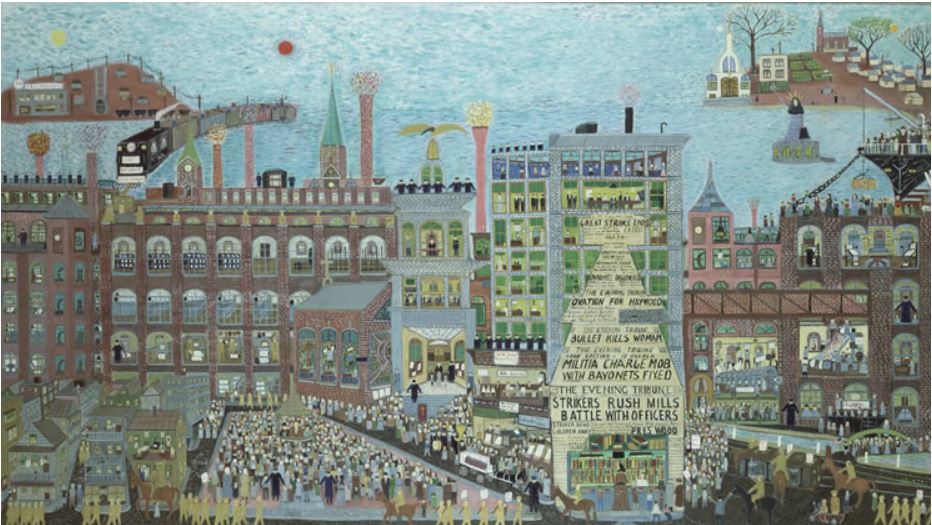

Brooke had his finger on the pulse of the nation. Before the outbreak of World War I, the British were proud colonialists, confident in their strength and proud of their ability to control an empire that stretched around the globe. But the Pax Britannia, the relatively peaceful world that Britain’s control had secured, weighed heavily on its restless and pampered youth, of which Brooke was one.

Brooke was born into a privileged family on August 3, 1887. He attended Rugby, where he was a head prefect and captain of the rugby team. At Cambridge University he studied Classics and moved in intellectual circles. After college he traveled to America and the South Seas and spent a year in Germany. His first book of poems, published in 1911, were not well received. However, one of his poems written in Germany in 1912 touched the hearts of the English and catapulted him into the limelight. The speaker in "The Old Vicarage, Grantchester," is a homesick Englishman who asks

“Stands the Church clock at ten to three?

And is there honey still for tea?"

When war broke out in August 1914, Brooke, like the rest of the nation, was ready to join. His sonnet, "Peace," demonstrates how war was welcomed by a youth whose life felt frivolous and void of meaning. Wanting to prove himself, he enlisted in the Royal Naval Reserve and saw some brief action at Antwerp in October 1914.

Brooke’s best-known poem, “The Soldier," was read from the pulpit on Easter Sunday 1915. The reader commented that “such enthusiasm of a pure and elevated patriotism had never found a nobler expression". On March 11, both the poem and the comment were repeated in The Times, and Rupert Brooke became Britain’s ideal handsome young warrior. His poems expressed the idealism, patriotic fervor, and romantic sacrifice that the public wanted.

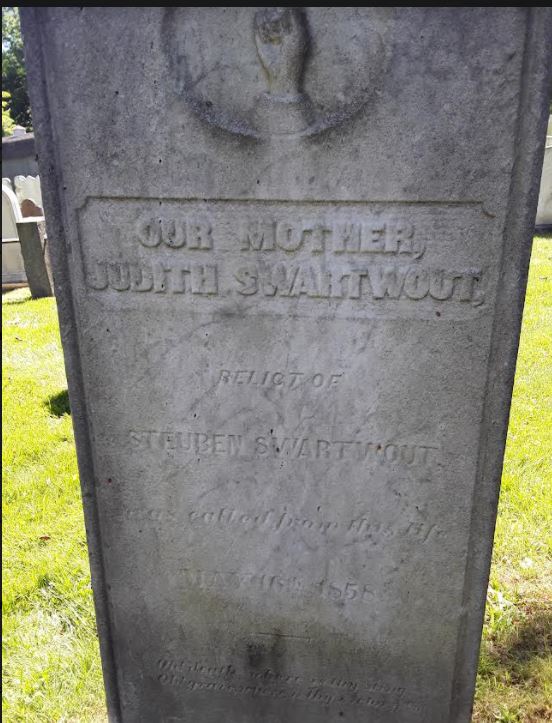

But Brooke would not live to hear the nation’s praises. He was sent east with the British Mediterranean Expeditionary Force at the start of the Gallipoli offensive. While sailing aboard the transport ship Grantully Castle, he was bitten on his lip by a mosquito. The bite festered, and he was transferred to a French hospital ship that was anchored off the island of Skyros. About a week after his poem was red, Brooke died, of septicemia or blood poisoning, on April 23 1915. His friends buried him in an olive grove on Skyros. He was only 27 years old.

A month after Brooke’s death, his friend Edward Marsh rushed the poems he had written in his last few months of life into print. Titled “1914 and Other Poems,” the collection included a romantic photo of him with bare shoulders and flowing hair that made many a woman swoon. Brooke became, according to Bernard Bergonzi, author of Heroes’ Twilight, the “quintessential young Englishman; one of the fairest of the nation’s sons; a ritual sacrifice offered as evidence of the justice of the cause for which England fought.” People as varied as Virginia Woolf and Winston Churchill paid him homage. First published in May 1915, the book was so popular that it had been reprinted 24 times by June 1918.

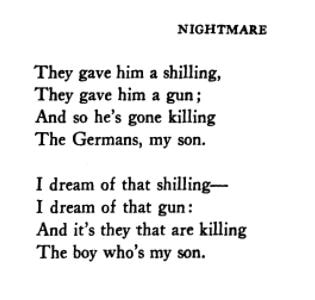

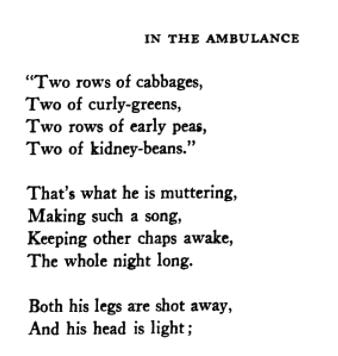

Brooke had expressed the sentiments of a nation anxious to show itself in war. As the war dragged on, the nation realized that it was not the glamorous, heroic show they had expected. Critics began to call Brooke’s poetry foolishly naive and sentimental, and harsher and more realistic poems began to grab the public imagination. There is little doubt that, had he lived longer and experienced some of the horrors other war poets did, Brooke’s poetry would have changed as well.

PeacE

Now, God be thanked who has matched us with his hour,

And caught our youth, and wakened us from sleeping!

With hand made sure, clear eye, and sharpened power,

To turn, as swimmers into cleanness leaping,

Glad from a world grown old and cold and weary;

Leave the sick hearts that honor could not move,

And half-men, and their dirty songs and dreary,

And all the little emptiness of love!

Oh! we, who have known shame, we have found release there,

Where there’s no ill, no grief, but sleep has mending,

Naught broken save this body, lost but breath;

Nothing to shake the laughing heart’s long peace there,

But only agony, and that has ending;

And the worst friend and enemy is but Death.

The Soldier

If I should die, think only this of me:

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England. There shall be

In that rich earth a richer dust concealed;

A dust whom England bore, shaped, made aware,

Gave, once, her flowers to love, her ways to roam;

A body of England’s, breathing English air,

Washed by the rivers, blest by suns of home.

And think, this heart, all evil shed away,

A pulse in the eternal mind, no less

Gives somewhere back the thoughts by England given;

Her sights and sounds; dreams happy as her day;

And laughter, learnt of friends; and gentleness,

In hearts at peace, under an English heaven.

Jennifer Bohnhoff lives and writes in the mountains of central New Mexico. Her latest book, A Blaze of Poppies, is the story of a young cowgirl struggling to keep the ranch during the tumultuous years leading up to and during World War I. It is available directly from the author and in paperback and ebook on Amazon.